This is the blog post version of a presentation I made for my team at Deputy. Enjoy!

This is a short blog post on using rebase in our git branches. This was inspired by some of the conversations we’ve had during retros and standups in Profile squad. What I want to achieve with this talk is for us to elevate our engineering practice by using version control.

If you ever share branches with other engineers then listen up!

Commits and Branches

Rebase is a useful feature of git which allows us to rewrite our commit history. The reason why rebase is a double-edged sword is that it introduces some risks into our workflow.

So what are commits exactly, why is it risky to rewrite them?

Git tracks changes in the codebase, and a commit is a unit of change. Each commit has a unique hash (sometimes we call it a SHA). Each commit is also linked to the previous commit, known as the “parent” commit.

When we talk about branches, we are referring to the “tip” of the branch, also known as the HEAD. A branch isn’t necessarily a collection of commits, rather it is a particular HEAD which has all the parent commits going back to the beginning of the repo.

We call them commits because they can’t be changed.

Every Commit is Unique

You can’t edit a commit, and you can’t duplicate one exactly — you can only duplicate the code changes that are part of the commit, but the SHA will always change.

Since all commits are linked to their parent, if you delete a commit, you must discard all the children.

Rebase

Rebasing is when we rewrite commits.

When you rebase something, you can think of it as moving your commits on to the tip of another branch.

Since this changes the parents of your commits, then all your commits are actually copies, with different SHAs.

To a human, the commit history will look very clean and linear. It can also be easier to follow the changes over time.

However, if you aren’t careful, you can get into strife. If any of the commits you copied are already public, then there will be consequences.

Consequences

If you move a public commit, you now need to convince everyone else who has that commit to do the same thing. If you want to push your commits, you need to use force push now.

Additionally, since the old version of the commit no longer exists, any metadata such as review comments will be orphaned. As a result, code review is more difficult.

If someone else pushes before you do, then force-pushing will overwrite their changes. That’s not very “stronger together” at all.

The Golden Rule

The golden rule of rebase is to only rebase commits that do not exist in the remote repo.

Remember that.

Grab a whiteboard marker and write it on your bathroom mirror so you can remind yourself every morning.

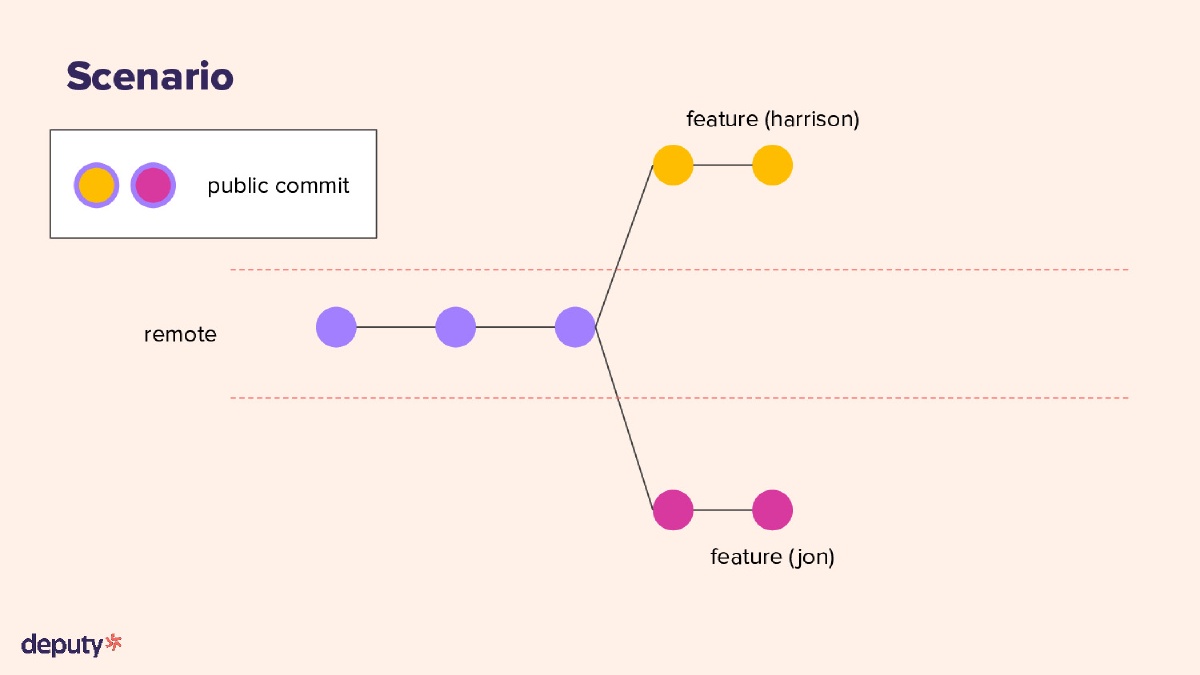

Scenario

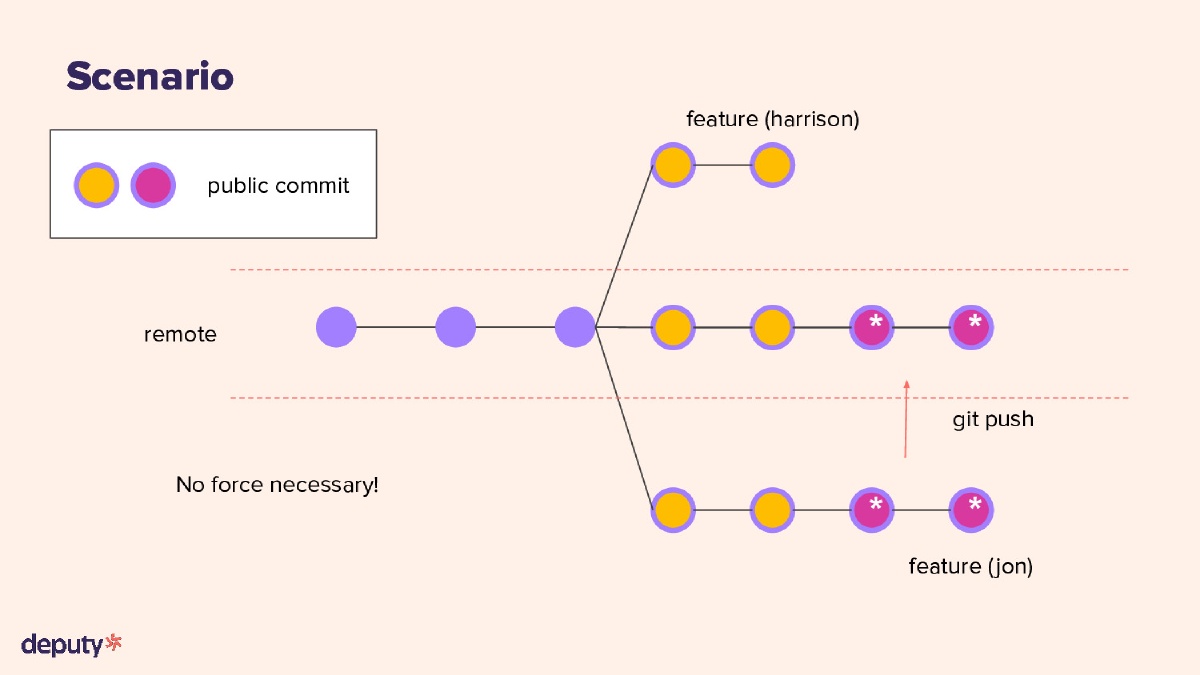

Let’s go through a correctly executed rebase scenario together.

Two engineers working on the same branch.

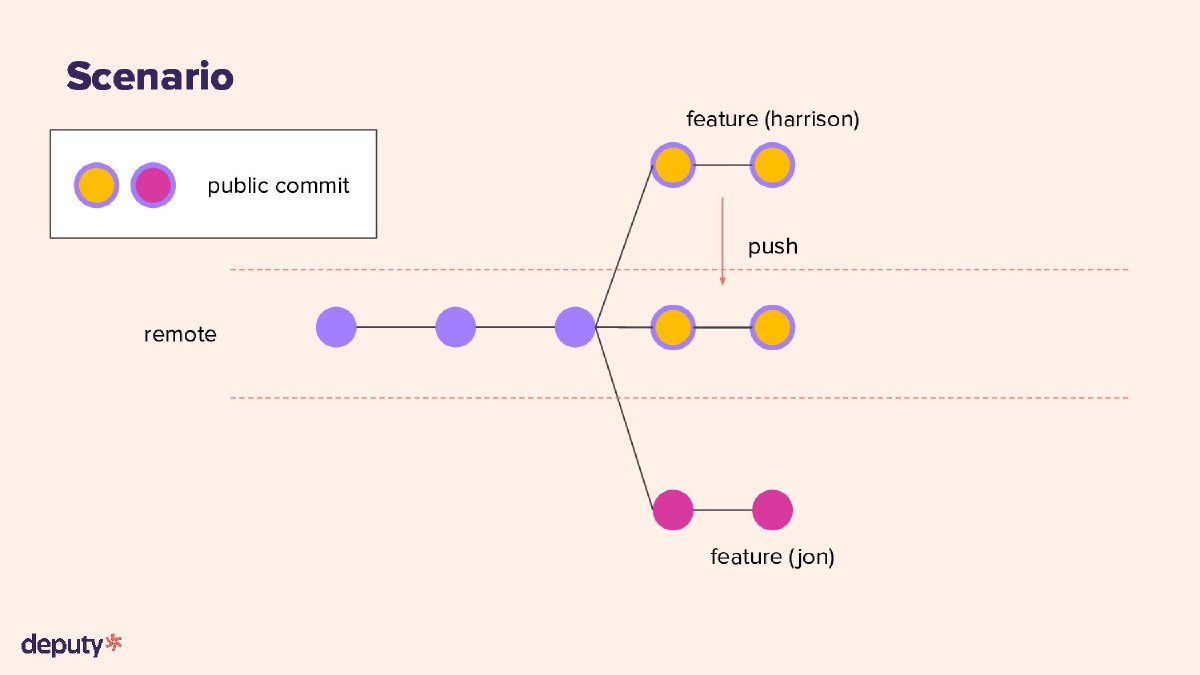

Harrison pushes his commits to remote.

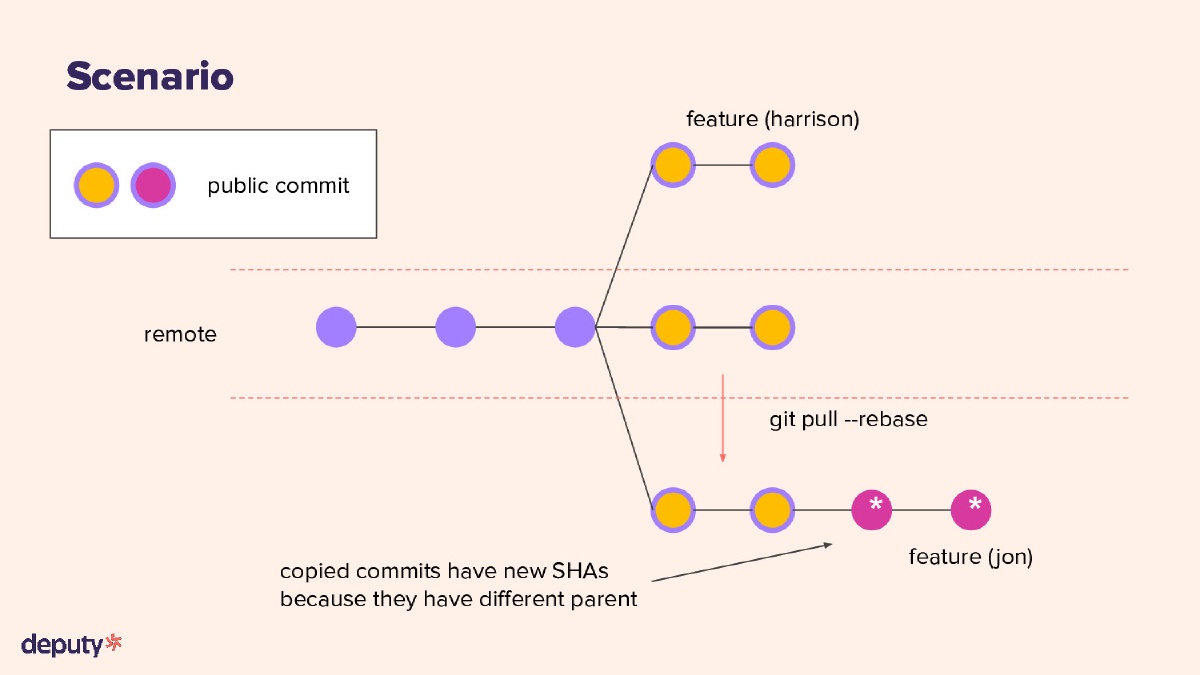

Jon uses git pull --rebase to move his own commits to the tip of the remote branch.

Jon pushes the new commits (with new SHAs) to remote, without forcing.

That’s a clean rebase! No --force necessary.

Just Use Merge

You can also just use merge and that’s fine as well. Probably easier too.

Thanks for reading!